💡 What You’ll Learn

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand that building a custom Spark streaming source isn’t rocket science. It’s actually a well-defined conversation between Spark and your code, with just 5 key methods to implement. We’ll use a real Ethereum blockchain streaming example to show you exactly how it works.

The Problem: You Have Data, Spark Wants It

You’ve got data streaming in from somewhere unique — maybe it’s IoT sensors, a blockchain, a custom message queue, or an internal database. You want to process it with Spark’s powerful distributed engine, but there’s no pre-built connector. What do you do?

The good news: You can build your own custom source. The even better news: It’s simpler than you think.

Real-World Use Case: In this guide, we’ll walk through streaming Ethereum blockchain data into Spark. The same principles apply to any data source — from proprietary APIs to custom databases. The pattern is universal.

The Secret: It’s Just a Conversation

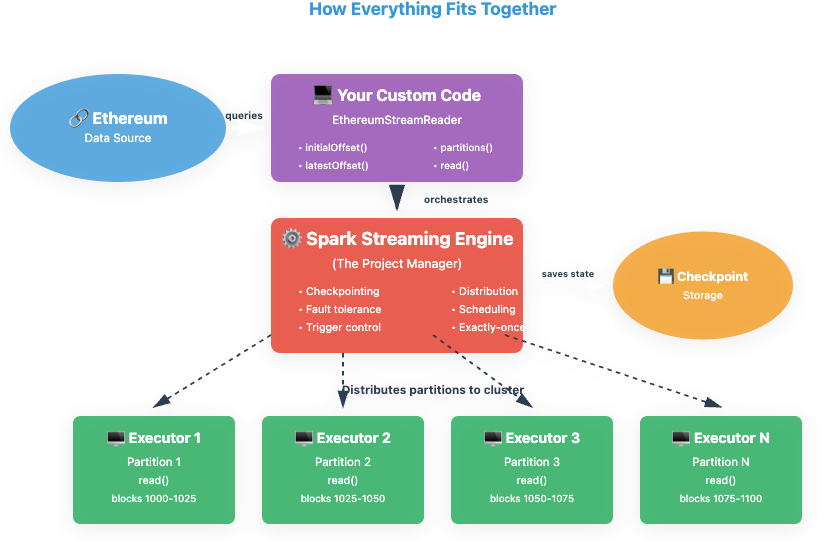

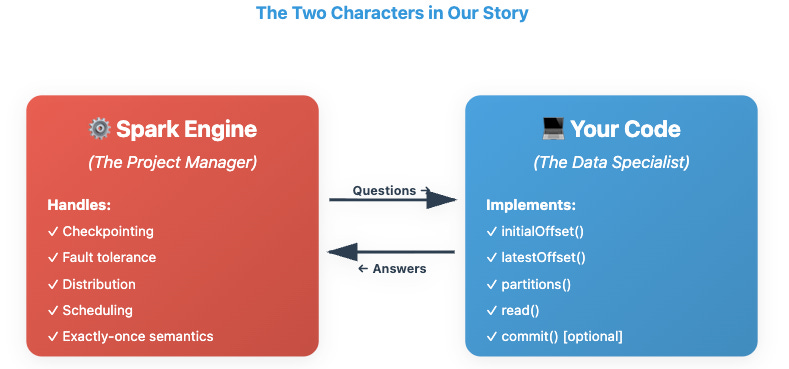

Think of building a custom Spark streaming source as a conversation between two specialists:

The Two Characters in Our Story

Spark’s job (the Project Manager) is to handle all the complex distributed computing stuff: checkpointing, fault tolerance, distributing work across a cluster, and guaranteeing exactly-once processing semantics.

Your code’s job (the Data Specialist) is much simpler: answer Spark’s questions about where your data is, how to access it, and how to break it into chunks that can be processed in parallel.

🎯 Key Insight: You don’t need to understand distributed systems, fault tolerance algorithms, or checkpoint mechanisms. You just need to implement 5 simple methods that answer Spark’s questions about your data source.

The 5 Questions Spark Will Ask You

Spark’s conversation with your code follows a predictable pattern. It asks 5 questions, and you provide straightforward answers. Let’s look at each one:

Let’s See Real Code: Streaming Ethereum Blocks

Theory is great, but let’s look at actual implementation. Here’s how these 5 methods work in practice for streaming Ethereum blockchain data:

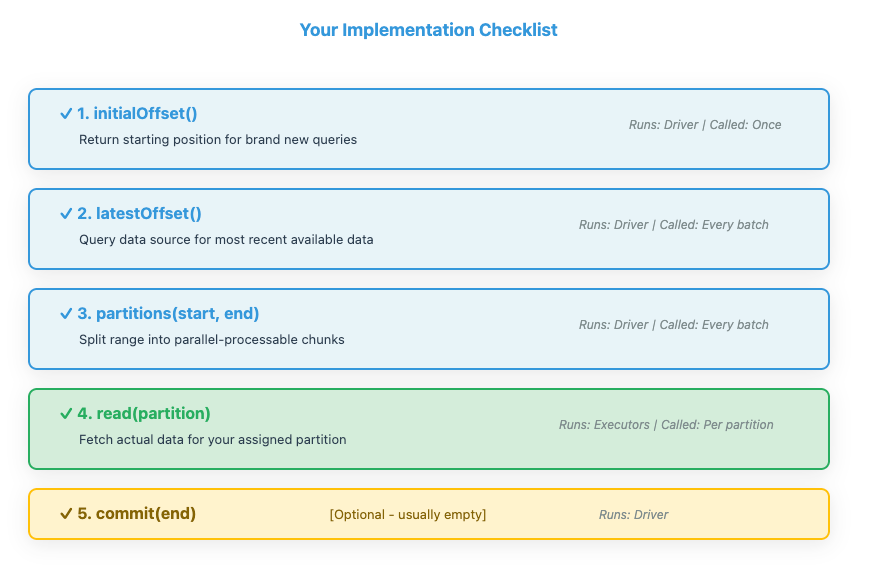

1. initialOffset() — Setting the Starting Point

def initialOffset(self) -> dict:

“”“

Called ONCE when starting a brand new query.

Return where to begin reading.

“”“

start_block = self.options.get(”start_block”, 0)

return {”offset”: int(start_block)}

That’s it! Just return a dictionary with your starting position. Spark saves this and uses it as the baseline for the entire query lifecycle.

2. latestOffset() — Checking What’s Available

def latestOffset(self) -> dict:

“”“

Called at the START of every batch.

Connect to your source and return the newest available data.

“”“

latest_block = self.w3.eth.block_number

return {”offset”: int(latest_block)}

This method connects to your data source (in this case, an Ethereum node) and asks “what’s the latest?” The answer defines the upper bound for the current batch.

⚠️ Python API Limitation: In PySpark,

latestOffset()must return the absolute latest data point. If you’re backfilling from very old data, your first batch could be huge. The Scala API offers more fine-grained control here, but for most real-time use cases, the Python API works perfectly.

📝 Note: This limitation is actively being addressed - there’s currently a pull request in progress to fix this in Spark.

3. partitions() — Dividing the Work

def partitions(self, start: dict, end: dict) -> list:

“”“

Spark gives you a range (start → end).

You break it into smaller chunks for parallel processing.

“”“

start_block = start[”offset”]

end_block = end[”offset”] # This is EXCLUSIVE (not included)

num_partitions = self.spark.conf.get(”spark.sql.shuffle.partitions”, “4”)

blocks_per_partition = (end_block - start_block) // int(num_partitions)

partitions = []

for i in range(int(num_partitions)):

partition_start = start_block + (i * blocks_per_partition)

partition_end = partition_start + blocks_per_partition

if i == int(num_partitions) - 1: # Last partition gets any remainder

partition_end = end_block

partitions.append(BlockRangePartition(partition_start, partition_end))

return partitions

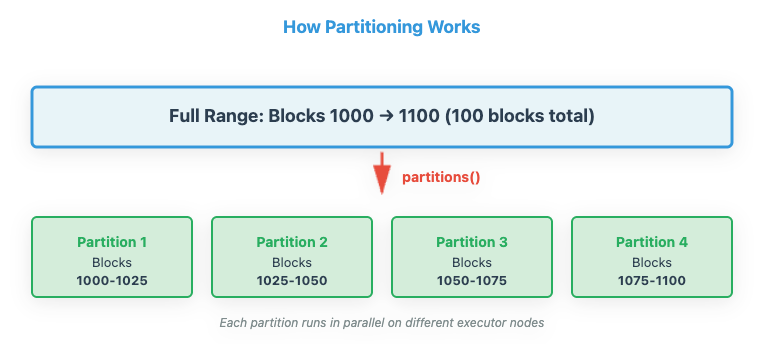

How Partitioning Works

s

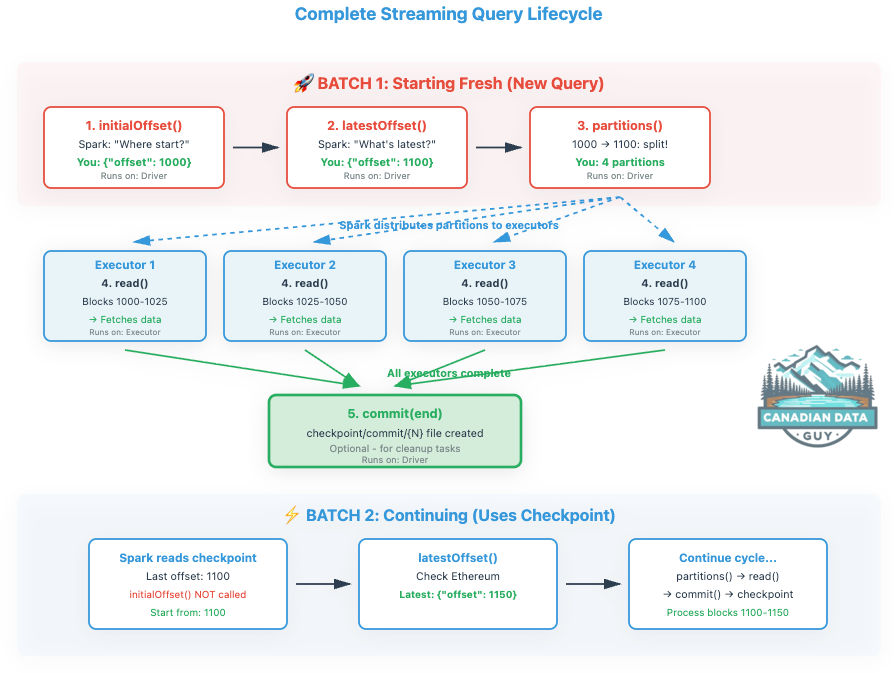

🔑 Critical Detail: Notice that the end block (1100) is exclusive. This means partition ranges are [1000, 1025), [1025, 1050), etc. Block 1100 is NOT processed—it becomes the start of the next batch. This [start, end) pattern is how Spark guarantees no data is ever processed twice.

4 read() — Actually Fetching the Data

def read(self, partition: BlockRangePartition):

“”“

This runs on EXECUTOR nodes (distributed across the cluster).

Each executor gets one partition and must fetch its assigned data.

Must be DETERMINISTIC - same input = same output, every time.

This allows Spark to safely retry failed tasks.

“”“

for block_number in range(partition.start_block, partition.end_block):

# Connect to Ethereum and fetch this specific block

block = self.w3.eth.get_block(block_number, full_transactions=True)

# Convert to Spark Row format

yield Row(

block_number=block.number,

block_hash=block.hash.hex(),

timestamp=block.timestamp,

transaction_count=len(block.transactions),

# ... more fields ...

)

This is where the real work happens! Each executor in your cluster runs this method for its assigned partition, fetching the actual data.

💪 The Power of Parallelism: If you have 10 executors and create 100 partitions, all 10 executors work simultaneously. Each one processes its chunk, and as executors finish, Spark automatically assigns them new partitions. This is how Spark achieves massive throughput.

5 commit() — Cleanup (Usually Empty)

def commit(self, end: dict):

“”“

Called AFTER all partitions successfully complete.

The checkpoint/commit/{N} file gets created at this point.

This method is optional - mainly used for cleanup tasks.

“”“

pass # Usually empty unless you need cleanup

In most cases, this method is empty. The checkpoint/commit/{N} file gets created automatically. You only need to implement this if you have cleanup tasks to perform after a batch completes.

The Complete Flow: Visual Walkthrough

Now let’s see how these methods work together in a complete streaming query:

Why This Design Is Brilliant

🛡️ Fault Tolerance

If an executor fails while reading blocks 1025-1050, Spark simply restarts that task on another machine. Because read() is deterministic, it fetches exactly the same data again. The user never knows a failure occurred.

⚡ Exactly-Once Semantics

The [start, end) exclusive range pattern means no block is ever processed twice. Block 1100 is the start of the next batch, not the end of the previous one. Combined with checkpointing, this guarantees exactly-once processing.

🚀 Massive Parallelism

By implementing partitions(), you tell Spark how to break work into chunks. Spark handles distributing those chunks to hundreds or thousands of executors. You get massive scale “for free.”

🧩 Separation of Concerns

You focus on your data source’s logic. Spark handles scheduling, distribution, checkpointing, fault recovery, and coordination. Clean boundaries make complex systems manageable.

What About Edge Cases?

Handling Source Failures

What if Ethereum node goes down during read()?

def read(self, partition: BlockRangePartition):

max_retries = 3

for block_number in range(partition.start_block, partition.end_block):

for attempt in range(max_retries):

try:

block = self.w3.eth.get_block(block_number, full_transactions=True)

yield Row(...)

break # Success!

except Exception as e:

if attempt == max_retries - 1:

raise # Let Spark handle the failure

time.sleep(2 ** attempt) # Exponential backoff

If retries don’t work, the exception bubbles up, Spark marks the task as failed, and restarts it on another executor. Eventually the source recovers and processing continues from the checkpoint.

Dealing with Large Batches

What if latestOffset() returns a huge number?

The Golden Rule: Your processing rate should be greater than your input rate. Ideally, aim for 10x faster processing than data arrival. This is the key design principle.

If you’re processing data faster than it’s arriving, Spark will naturally catch up with any backfill over the next few batches. You don’t need to worry about temporarily large batch sizes.

About spark.sql.shuffle.partitions: You can adjust this, but don’t set it to an extremely high number. A reasonable partition count is sufficient as long as your processing rate exceeds your input rate.

Ensuring Determinism in read()

The golden rule: Same partition input must produce same output.

Bad (non-deterministic):

# ❌ DON’T DO THIS

def read(self, partition):

current_time = time.time() # Different each time!

yield Row(timestamp=current_time, ...)

Good (deterministic):

# ✅ DO THIS

def read(self, partition):

block = self.w3.eth.get_block(partition.block_number)

yield Row(timestamp=block.timestamp, ...) # Block timestamp is consistent

The Complete Picture: Architecture

🎯 You’re Ready to Build Your Own!

You now understand the complete lifecycle of a custom Spark streaming source. It’s not magic—it’s a well-designed conversation between Spark and your code.

Just implement 5 methods, and Spark handles the rest: fault tolerance, distribution, checkpointing, and exactly-once semantics.

Quick Reference: The 5 Methods

Your Implementation Checklist

Final Thoughts: Why This Matters

The beauty of this architecture is its universality. Whether you’re streaming from Ethereum, MongoDB, a proprietary API, or carrier pigeons 🐦, the pattern is the same:

Define where to start (

initialOffset)Check what’s new (

latestOffset)Break work into chunks (

partitions)Fetch the data (

read)Confirm completion (

commit)

Spark handles everything else—checkpointing, distribution, scheduling, fault recovery. You just focus on the specifics of your data source.

🚀 Take Action

The barrier to entry is lower than you thought. Pick a data source you’re working with, implement these 5 methods, and you’ll have a production-ready Spark streaming source in an afternoon.

Start small: Get initialOffset() and latestOffset() working first. Then add partitions() and read(). Test with a single partition before scaling up. You’ve got this! 💪

Now go build something amazing with Spark Streaming. The data world is your oyster. 🌊

![1initialOffset() — “Where do we start?”Spark asks: “This is a brand new query. Where should I begin reading?”You answer: {”offset”: 1000} — “Start at block 1000”2latestOffset() — “What’s the newest data?”Spark asks: “What’s the most recent data available right now?”You answer: {”offset”: 1100} — “Latest block is 1100”3partitions() — “How do we split this work?”Spark asks: “We need to process blocks 1000-1100. Break this into parallel chunks”You answer: [Partition(1000-1025), Partition(1025-1050), ...] — “4 chunks of 25 blocks”4read() — “Fetch the data!”Spark tells each worker: “Here’s your chunk. Go get the actual data”You fetch: Loop through blocks 1000-1025, fetch each one, yield Row objects5commit() — “All done!” [optional]checkpoint/commit/{N} file created. Optional method for cleanup tasks. 1initialOffset() — “Where do we start?”Spark asks: “This is a brand new query. Where should I begin reading?”You answer: {”offset”: 1000} — “Start at block 1000”2latestOffset() — “What’s the newest data?”Spark asks: “What’s the most recent data available right now?”You answer: {”offset”: 1100} — “Latest block is 1100”3partitions() — “How do we split this work?”Spark asks: “We need to process blocks 1000-1100. Break this into parallel chunks”You answer: [Partition(1000-1025), Partition(1025-1050), ...] — “4 chunks of 25 blocks”4read() — “Fetch the data!”Spark tells each worker: “Here’s your chunk. Go get the actual data”You fetch: Loop through blocks 1000-1025, fetch each one, yield Row objects5commit() — “All done!” [optional]checkpoint/commit/{N} file created. Optional method for cleanup tasks.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LND2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F403de673-2c13-4cba-bd3a-5fabd03f3d14_828x662.png)